what happened to american defense spending under president reagan?

Nov 8, 2017 |Katherine Blakeley

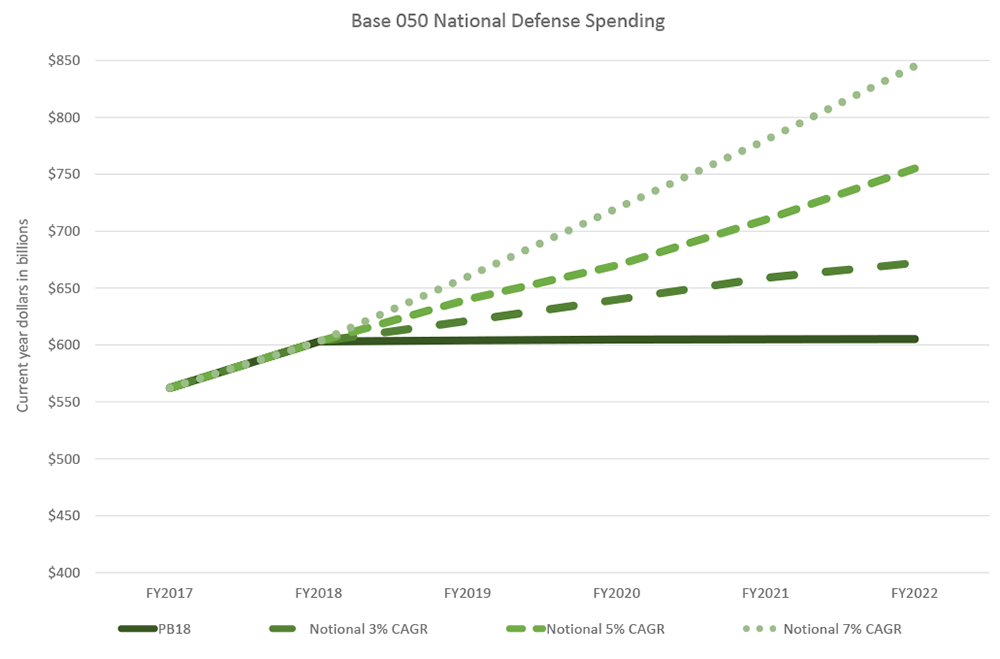

Shifts in the international security environment, as well every bit calls by the Trump assistants for a "historic" defense increase, have led analysts, Congressional leaders, and senior Pentagon officials to hope for or expect a defense buildup commensurate with the Reagan-era buildup of FY 1979–FY 1985. Secretarial assistant of Defense James Mattis and House Military machine Commission Chairman Mac Thornberry (R-TX) accept chosen for, at a minimum, sustained five percent annual increases to the defense budget above the FY 2018 request.[ane] Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Joseph Dunford stated in testimony that the capabilities to support the forthcoming National Defence force Strategy would require the defense budget to grow by between 3 and seven percentage annually through FY 2023. Even and so, this increased level of funding would not let the military to increase the size of the strength.[ii] Analysts are banking on 4–six per centum annual growth in procurement funding, down from more aggressive expectations of high single-digit or low double-digit growth espoused presently after the election in 2016.[three] Although there are some important parallels between the early 1980s and today, there are likewise some disquisitional differences that make an equivalent defense force buildup less likely to occur.

Offset, defense spending is shaped by the perceived demands of our national security in a shifting and challenging international security environs filtered through political considerations; information technology should not exist an arbitrary round number or percent of GDP. The Reagan-era buildup occurred in against the groundwork of wide bipartisan perception of an increasingly unfavorable U.S. position in its bipolar strategic competition with the USSR. By contrast, national security practitioners and policymakers have only recently begun to recognize the electric current shift from the unipolar security environment of the postal service-Cold War era to an era of renewed contest with Russia and Mainland china, as well as other challenges to the U.Due south.-led international order, and there is equally yet no consensus as to its key features.[4]

Appropriately, there is not notwithstanding a shared understanding of the types of military strategies and capabilities that will be about important to the United States in this increasingly challenging surroundings. Decisions about what investments in military capabilities may be needed (for example, a more than robust U.S. military and allied presence in Eastern Europe with heavy brigades, footing-based fires, greater airpower, and capabilities to operate in a high-terminate contested gainsay surroundings) or the appropriate residual between high- and low-cease capabilities in the Air Force and Navy, and therefore the level of defense spending that may be required, should be grounded in a clear vision of the international security surround, U.S. objectives, and the role of our allies and partners. Additionally, this epochal shift in the international security environs demands a corresponding focus on longer-term thinking about U.South. strategy, capabilities, and defense budgets, struggling confronting the tyranny of immediacy imposed by national security crises, domestic political calculations, and near-term bureaucratic victories in the budget procedure.

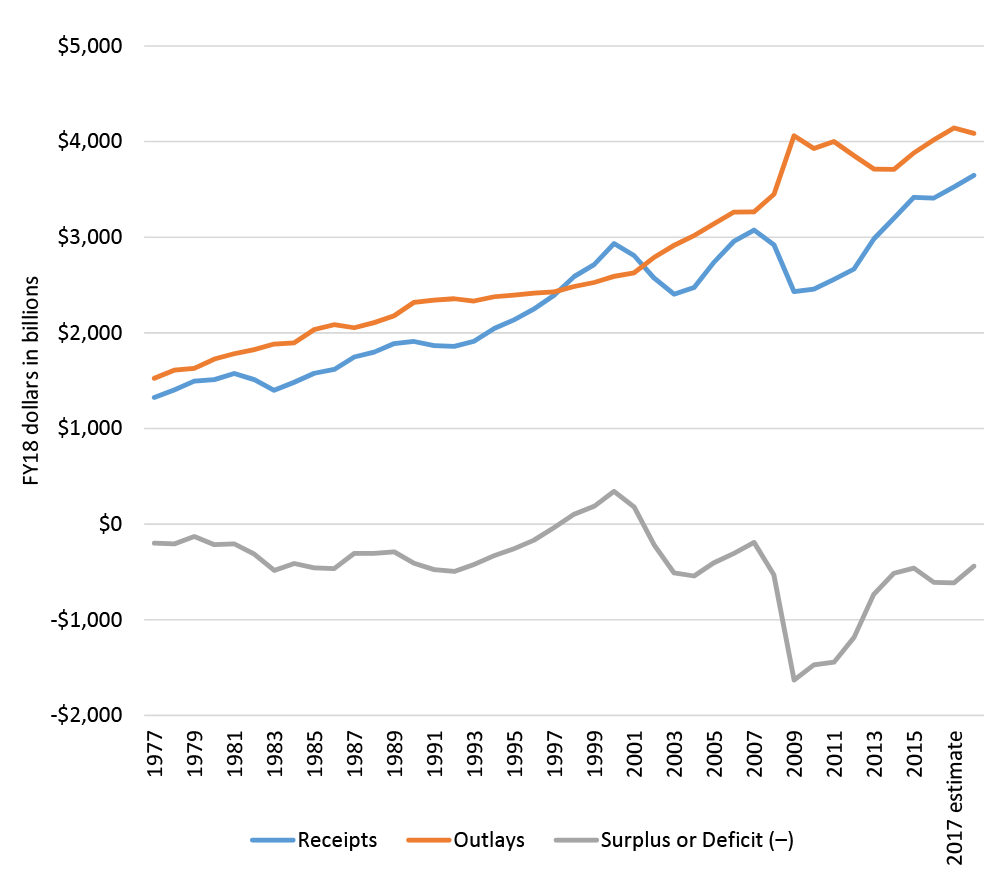

Secondly, the contemporary defense spending monetary landscape is very different than it was during the Reagan-era buildup. The chop-chop increasing defense budgets of FY 1979–FY 1985 were financed predominantly through deficit spending, every bit the Reagan administration cut taxes in 1981, decreasing revenues in both accented and relative terms (see Figure 9-1).[5] The rapid growth of the deficit and rising outlays led to the enactment of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Balanced Budget Deed of 1985. This law, the grandfather of the electric current Upkeep Command Act of 2011, imposed caps on overall discretionary spending levels in an effort to reduce the federal deficit. The Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act finer halted the Reagan administration's defense buildup, and defense spending contracted rapidly after the FY 1985 high water mark. By contrast, the gimmicky BCA is already in force, and has placed caps on defense and non-defense force spending through FY 2021 that are enforced by the sequester mechanism borrowed from the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act, smothering a prospective defence force buildup. Although Congress has reached a bipartisan deal to meliorate the defense caps each year since FY 2013, the average corporeality of and so-called sequester relief has been $18 billion in FY 2018 dollars, reflecting the narrow boundaries for compromise between the fiscal hawks, mainline Republicans, and Democrats. Without an agreement to substantially raise or eliminate the BCA caps, any growth in defense spending will be far beneath a comparable buildup in either total amounts or rate of growth.

Effigy ix-1: Federal Receipts, Outlays, and Surplus or Arrears, FY77–FY18

Source: OMB, Historical Tables, Upkeep of the United States Government, Financial Year 2018 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2017), Table i.3, "Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-) in Current Dollars, Constant (FY 2009) Dollars, and as Percentages of Gross domestic product: 1940–2022," bachelor at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/hist01z3.xls. Calculations by CSBA.

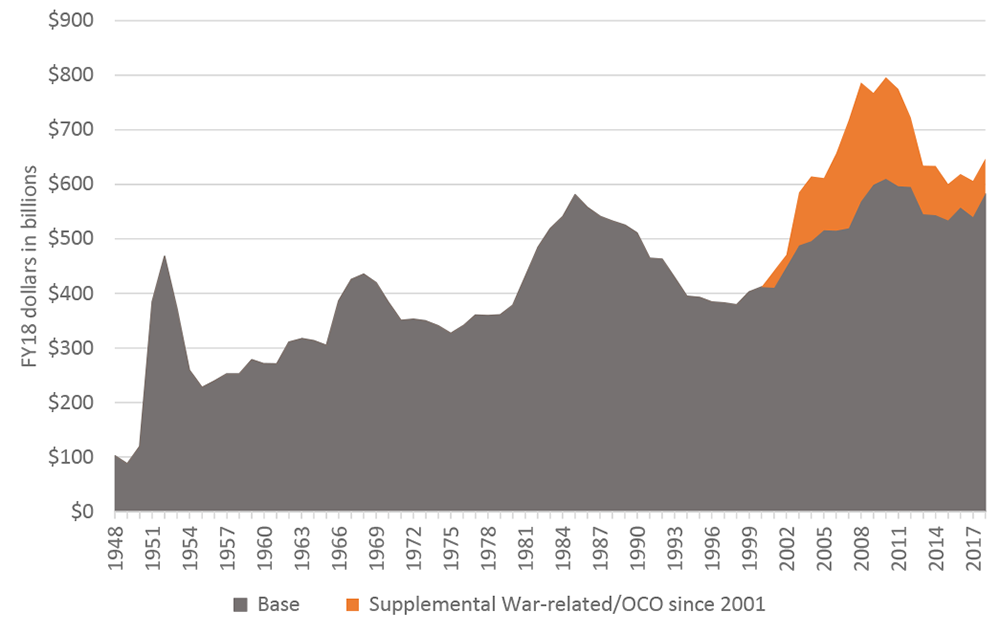

Third, total DoD budgets have exceeded those of the Reagan-era defence buildup since FY 2003, prompting some to inquire why even higher defence force spending is justified and what we're collectively getting from our national spending on defense. In an annual Gallup survey for 2017, 31 percent of Americans surveyed felt that the U.South. was spending "too much" on defence force.[6] The FY 2018 DoD budget request of $647 billion (including base, OCO, and mandatory spending) is $65 billion, or 11 percent, more than than the $581 billion defense budget at the peak of the Reagan buildup. Fifty-fifty excluding Overseas Contingency Operations funding, the base defense budget request still matches or exceeds the average funding levels of the Reagan-era buildup later adjusting for inflation. The FY 2018 base budget request of $582 billion (including both discretionary and mandatory spending) is slightly higher than the peak of the Reagan buildup of $581 billion in FY 1985 and $59 billion, or xi per centum, more than the boilerplate DoD budget of $523 billion during the Reagan Administration.

DoD's largest total budget, at $796 billion, was in FY 2010 during the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It included $610 billion in base defense spending—$29 billion more than the $581 billon at the peak of the Reagan-era buildup—likewise as an additional $186 billion in OCO funding. Defense spending declined rapidly post-obit the drawdown of deployed forces in Iraq and Transitional islamic state of afghanistan and the imposition of caps on base discretionary defense spending by the Budget Command Act (BCA) of 2011. Despite the decline, full national defense funding at the lesser of the drawdown in FY 2015 was $628.9 billion, $32 billion more than the $596.9 billion spent on national defense during the top of the Reagan-era defense buildup, later on adjusting for inflation. The base of operations defense force upkeep in FY 2015, at $534 billion, was $11 billion or ii pct more than than the boilerplate base defense upkeep level during the Reagan-era buildup, although it remained below the peak base of operations budget of $581 billion in FY 1985 by $47 billion (see Figure nine-2).

Figure 9-2: Total DOD Base and OCO Spending, FY48–FY18

Source: OUSD (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2018, FY 2018 Greenbook (Washington, DC: DoD, June 2017). Calculations by CSBA.

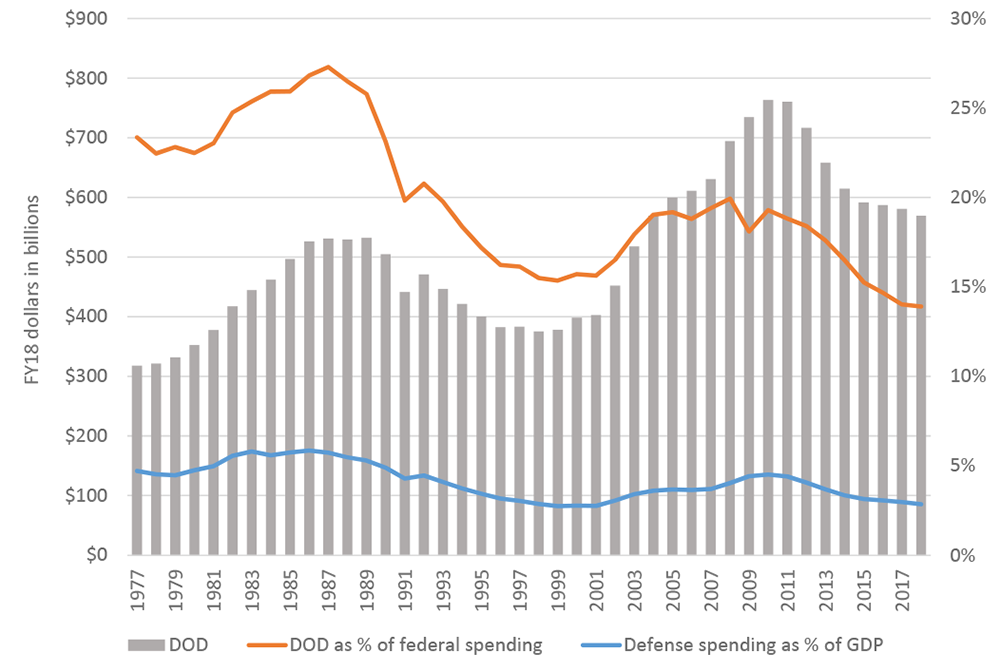

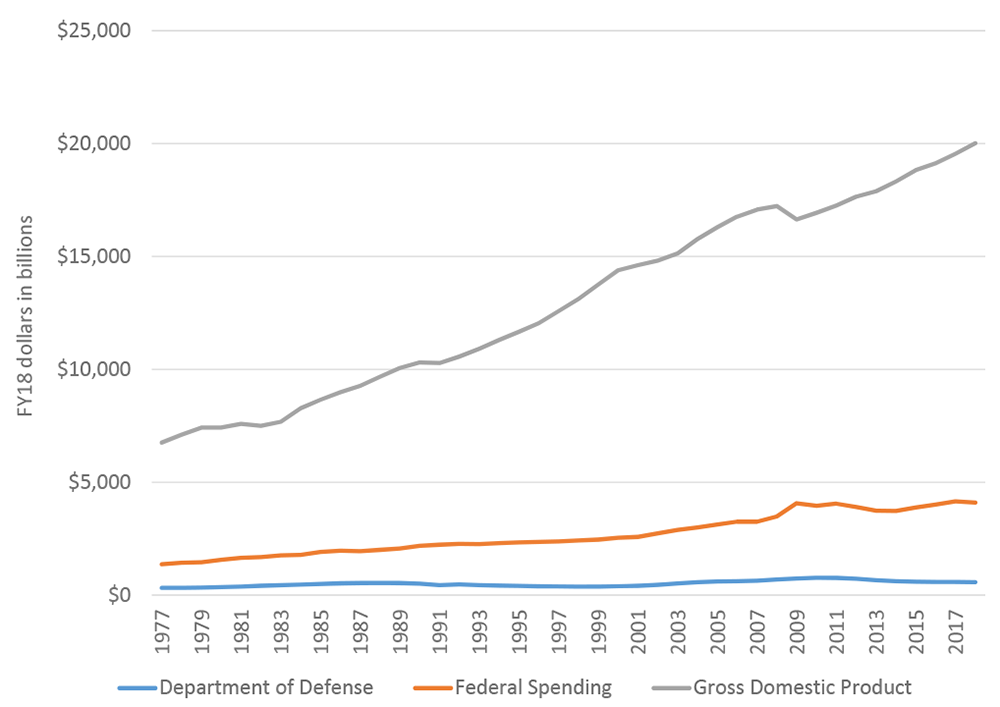

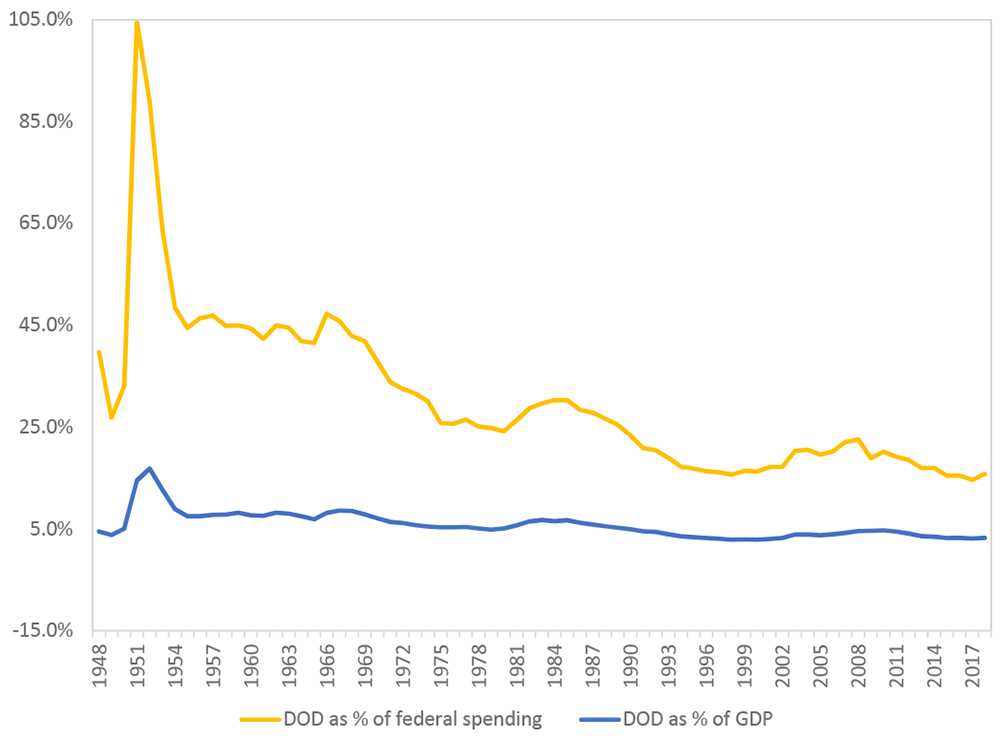

Overall, the share of defense spending as a pct of GDP has declined steadily since the end of the Korean War. The U.S. national Gross domestic product grew from $two.27 trillion in FY 1948 to an estimated $20.0 trillion in FY 2018 in constant dollars—a cumulative annual growth rate (CAGR) of iii.2 percentage. Over the same fourth dimension period, defence force spending has risen from $102 billion in FY 1948 to a requested $646 billion in FY 2018 for a CAGR of 2.7 percent (see Figure 9-four and Figure 9-5). Although total defense spending over the past xv years has reached historic highs in absolute terms, it represents a historically low per centum of Gross domestic product. Although not useful for gauging the necessity of defense spending, defense spending equally a percentage of Gross domestic product or as a percent of overall federal spending can be a useful yardstick in discussing the relative affordability of spending on defense—or any other federal programme. Spending a lower pct of Gdp on defense indicates that national security consumes a relatively small proportion of overall national economic activity, compared to the FY1979–FY 1985 defense buildup. Similarly, defence spending'southward relatively low share of federal spending in historical terms indicates that more money could be allocated to defense, if the political will to do so existed.

Funding for the Department of Defence force peaked at 30 percent of federal spending in FY 1983–FY 1985, when information technology was equivalent to half-dozen.7 pct of Gross domestic product (see Figure 9-3). In FY 2017, defense force outlays were $581 billion, higher than outlays during the summit of the FY 1979–FY1985 buildup, merely defense spending was a much lower 14 percent of federal spending and 3 percent of GDP. From an overall affordability perspective, the nation could increase spending on national defense considerably in dollar terms, while remaining beneath by proportions of defense spending as a share of GDP or federal spending. Spending the equivalent of 6.7 pct of GDP on the Section of Defense in FY 2018 would result in a DoD upkeep of $one,341 billion, while allocating 30 percent of federal spending to the DoD would event in a budget of $1,228 billion. This would exist an increase of $459 to $534 billion over the total FY 2018 DoD asking of $647.

Figure 9-iii: Defence Spending in Absolute and Relative Terms, FY77–FY18

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations past CSBA.

Figure ix-4: Gross domestic product, Federal Spending, and DOD Budgets

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations by CSBA.

Figure 9-5: DOD Budgets as a Percentage of Federal Spending and Gdp

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations by CSBA.

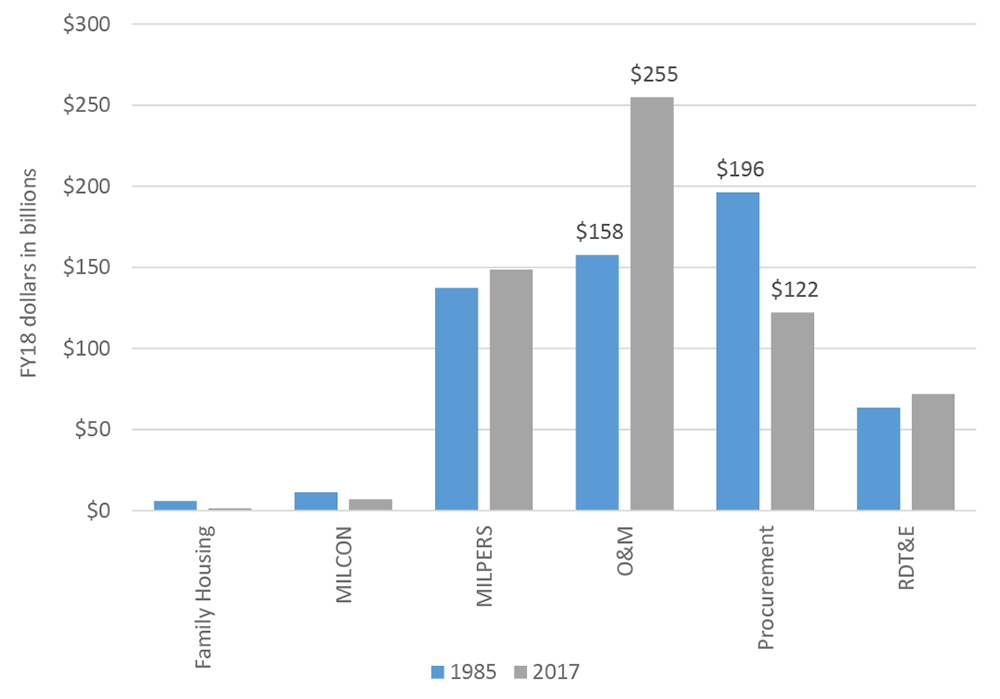

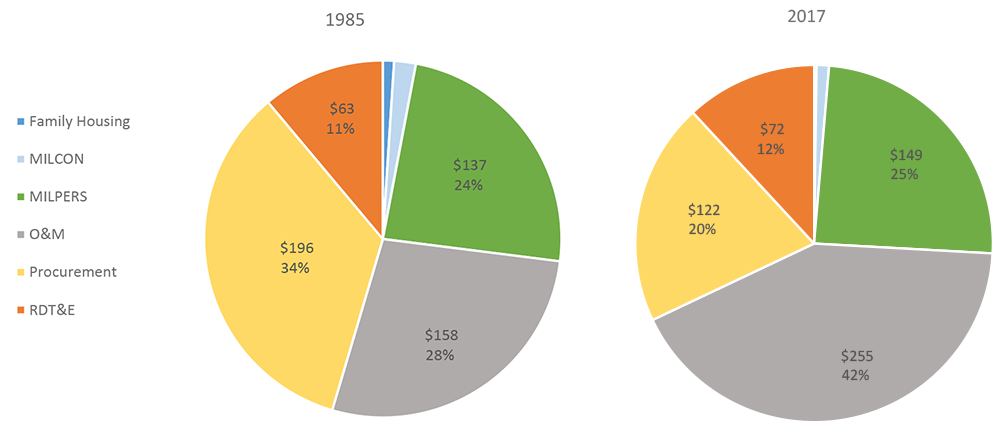

Across the topline figures, a dollar of defense force funding in the 1980s was spent much differently than a dollar of the defense budget today. Appropriately, even an equivalent expenditure would not yield an equivalent force structure. At the peak of the Reagan-era defense buildup in FY 1985, the Pentagon was spending 34 percentage of its budget on procurement and 11 pct on RDT&E, for a total of 45 percent on what is oftentimes termed "modernization." By contrast, modernization only received 32 per centum of defence spending in FY 2017, with procurement accounting for 20 per centum and RDT&Eastward 12 per centum. After adjusting for aggrandizement, procurement spending was $196 billion in FY 1985, simply just $122 billion in FY 2017—38 pct less (see Figure 9-6 and Effigy 9-seven).

Figure nine-half-dozen: Defense Spending past Appropriations Title, FY85 and FY17, in FY18 Dollars

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations by CSBA.

Effigy 9-seven: Composition of Defence force Budget in FY85 and FY17 by Appropriations Title

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations by CSBA.

Note: FY 2018 dollars in billions.

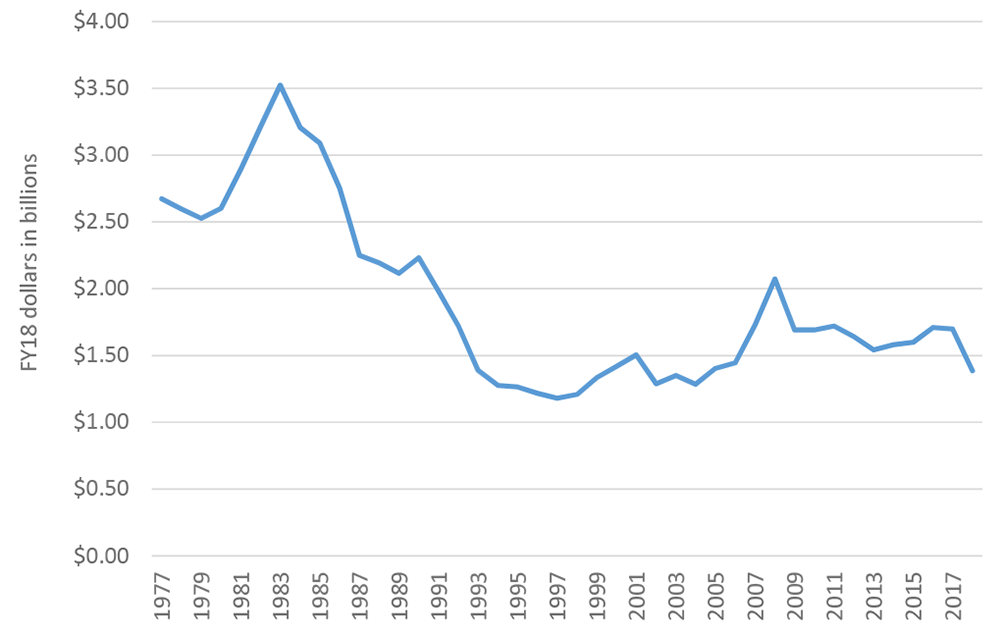

Figure ix-viii: Ratio of Procurement vs RDT&East Funding

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations by CSBA.

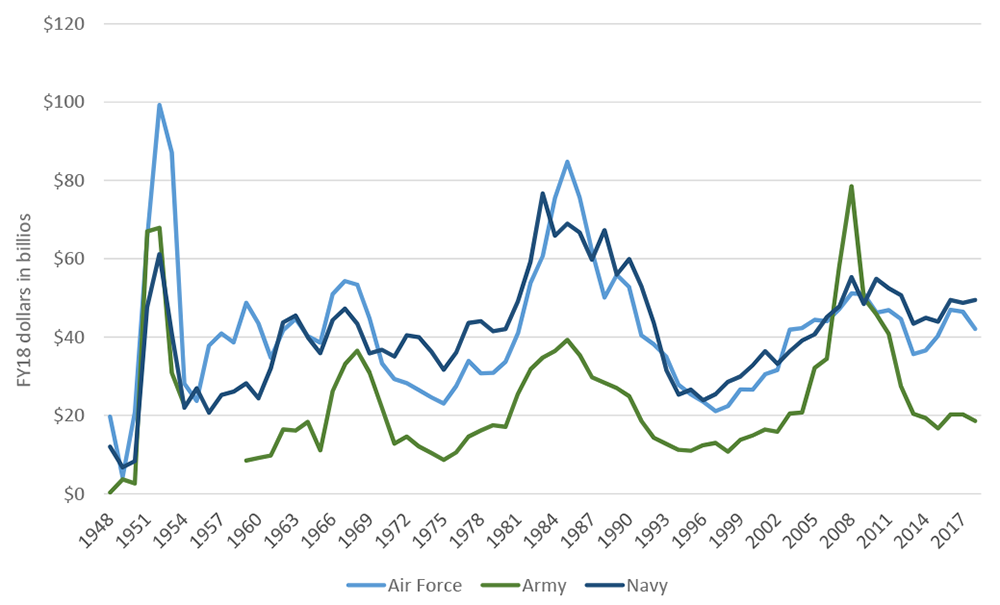

With the exception of the Army's procurement spike during the Republic of iraq and Afghanistan wars, principally for Mine-Resistant All-Purpose (MRAP) vehicles, Service procurement in the 2000s and 2010s was far beneath the Reagan-era average. From FY 1979 to FY 1992, Air Force procurement averaged $53.9 billion in FY 2018 dollars, whereas Navy procurement averaged $57.8 billion. Between FY 2003 and FY 2017, the Air Strength's procurement averaged $44.four billion, $ix.5 billion less annually than during the FY 1979–FY 1992 period; the Navy's procurement averaged $46.8 billion, $11 billion less annually. This decade and a half of missing procurement is a major reason why the armed forces is however relying on Regan-era systems for the bulk of the currently-fielded strength structure, and why it faces hard tradeoffs between maintaining and modernizing older equipment and purchasing new systems with the same scarce dollar.

Figure 9-9: Procurement Funding past Service

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations by CSBA.

Procurement and RDT&Due east has increasingly been crowded out past long-term increases in O&Yard costs. A dollar of defense spending in FY 2018 buys less forcefulness structure than a dollar of defense spending did in FY 1983. Putting it another mode, it has get costlier to maintain the same size force over time. Although mod systems are more capable than their predecessors, quantity is still required to perform many missions. This issue is highlighted by the strain that low ship numbers and high operational tempo take put on the surface Navy. Similarly, high operational tempo and maintenance and readiness challenges caused by a smaller, aging fleet are faced past U.S. gainsay air forces.

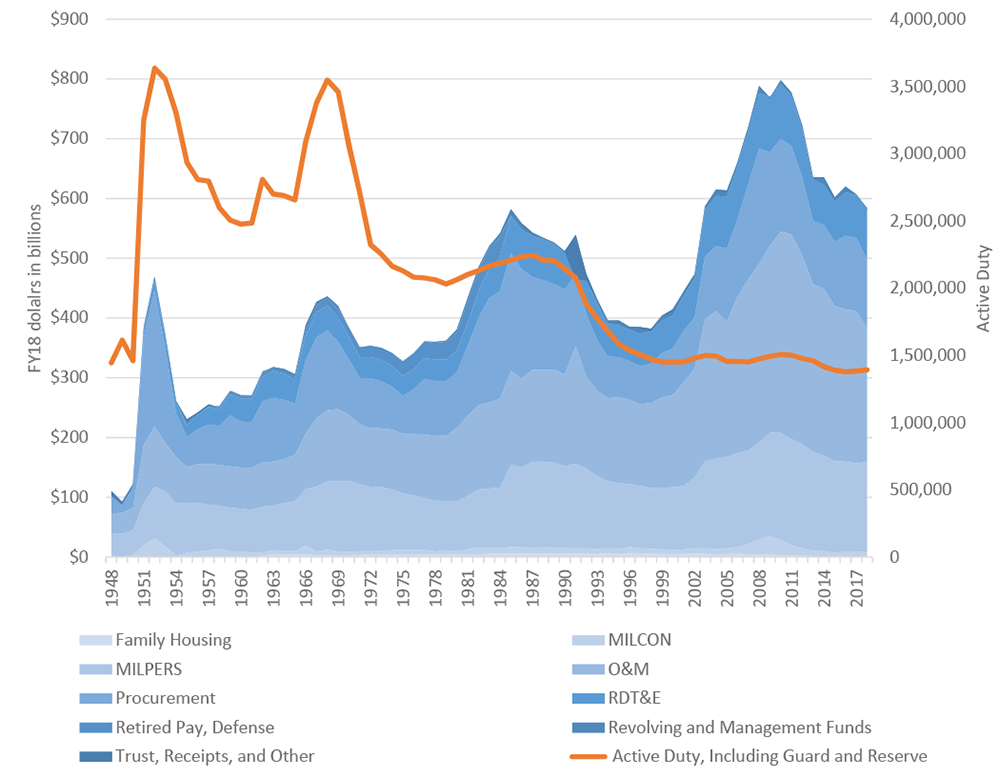

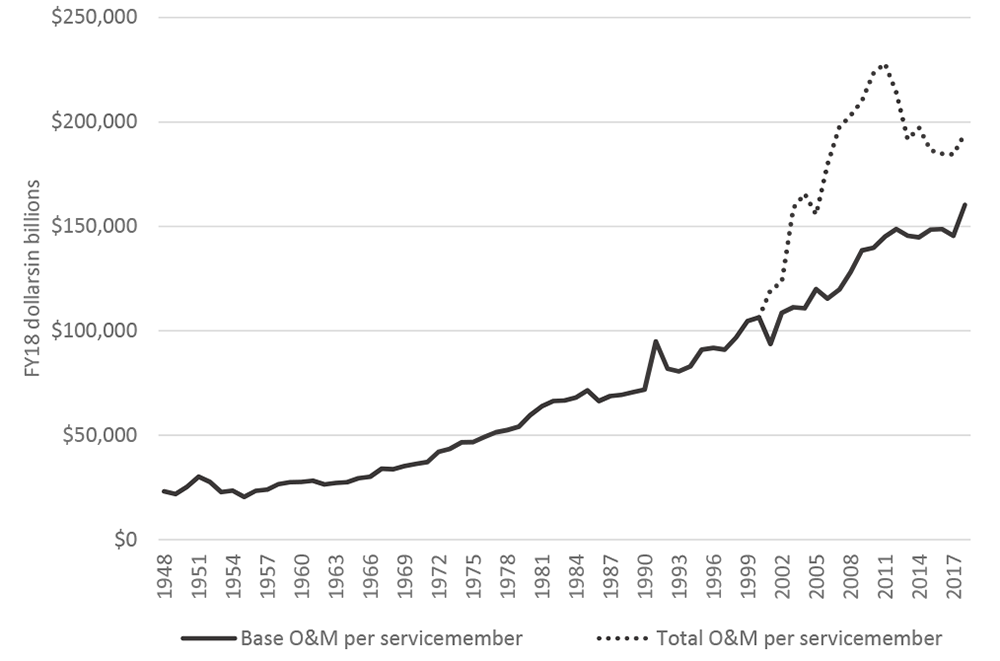

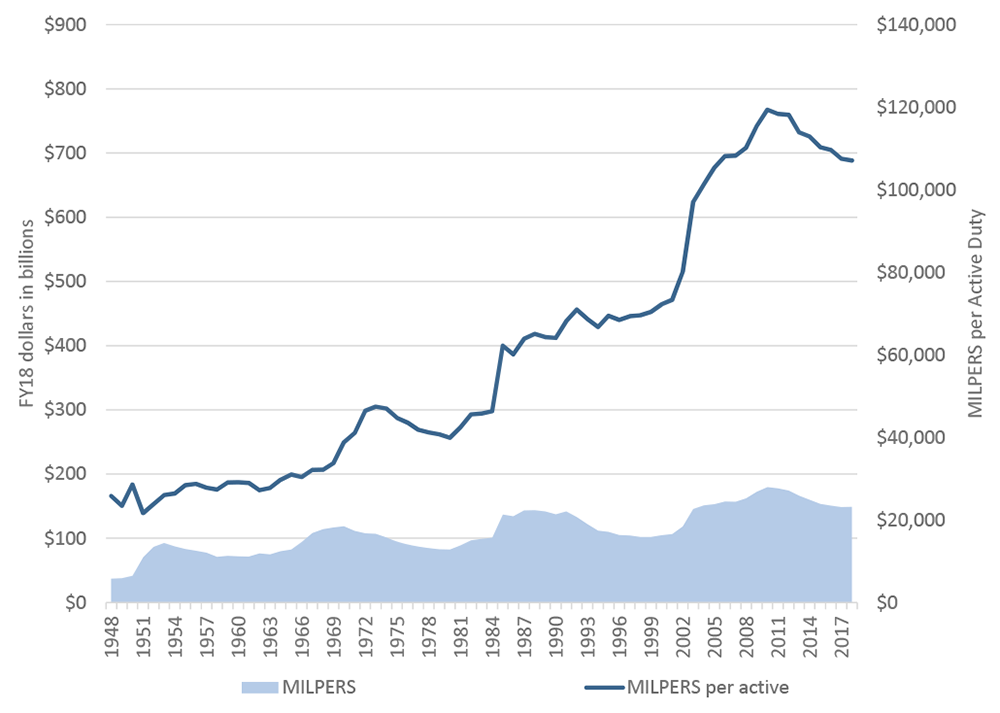

Spending on O&Grand and military machine personnel costs has grown in both existent terms and every bit a percentage of the defence force budget, fifty-fifty every bit the number of agile-duty personnel has trended downwards since the 1970s (run into Figure ix-10). Since FY 1948, base budget O&M has grown past 2.7 percent annually over aggrandizement. Since FY 2000, base budget O&Chiliad has grown by a CAGR of 2.1 percentage, growing from $106,380 per agile duty servicemember to $160,284 in FY 2018. Factoring O&M into war funding, total O&1000 has grown by a CAGR of three.2 percent over inflation to $194,544 per active duty servicemember (run into Figure nine-11). Similarly, the amount of armed services personnel funding per active duty servicemember or activated reservist has grown steadily as pay and benefits take increased. DoD now budgets $107,106 in military machine personnel funding for each active duty servicemember, a cumulative increase of 2.two percentage annually from $72,212 in FY 2000 (run across Effigy ix-12).

Effigy nine-x: Defense Spending by Appropriations Title and Active Duty Servicemembers

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations past CSBA.

Figure 9-11: O&M Funding per Active Duty Servicemember

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations past CSBA.

Figure ix-12: Military Personnel Funding and Military Personnel Funding per Agile Duty Servicemember

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations by CSBA.

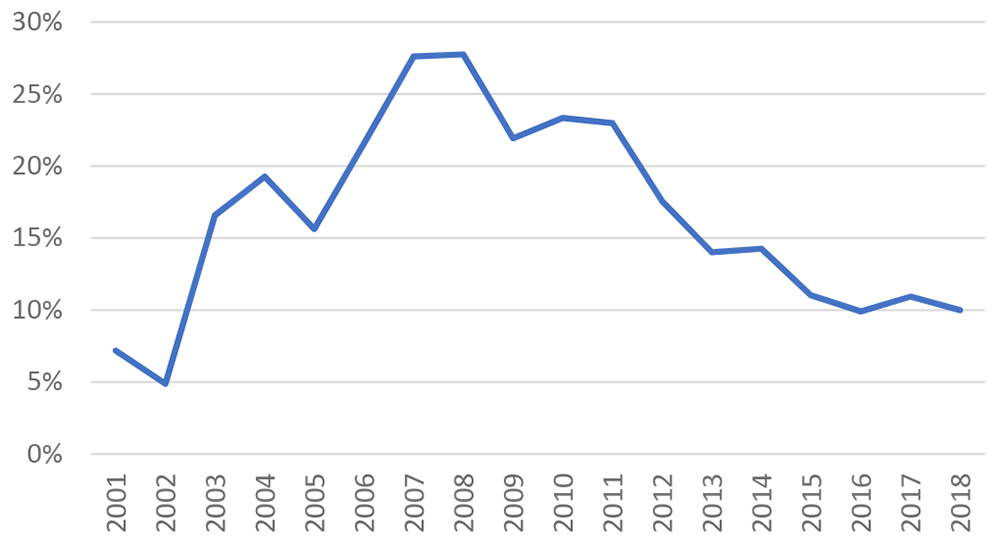

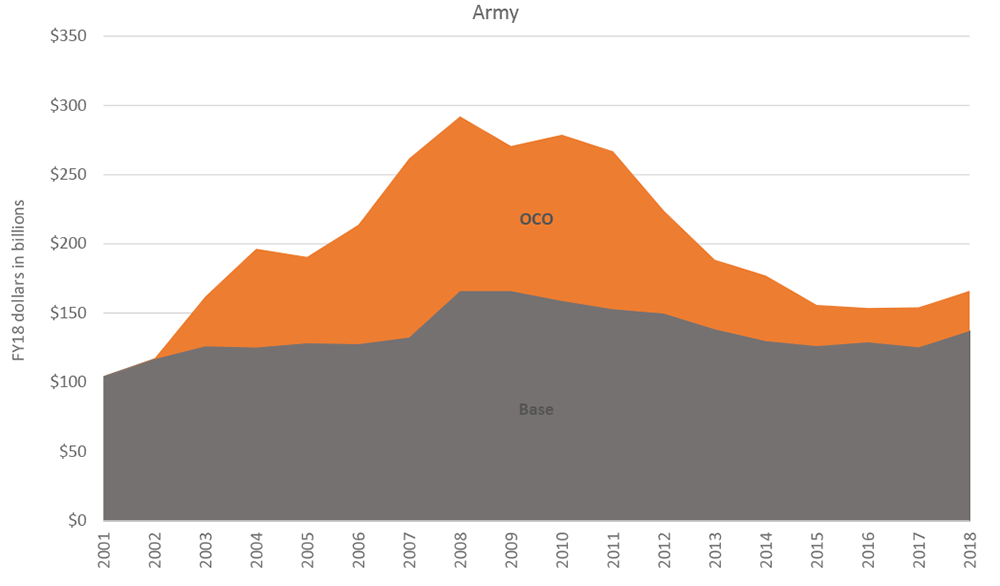

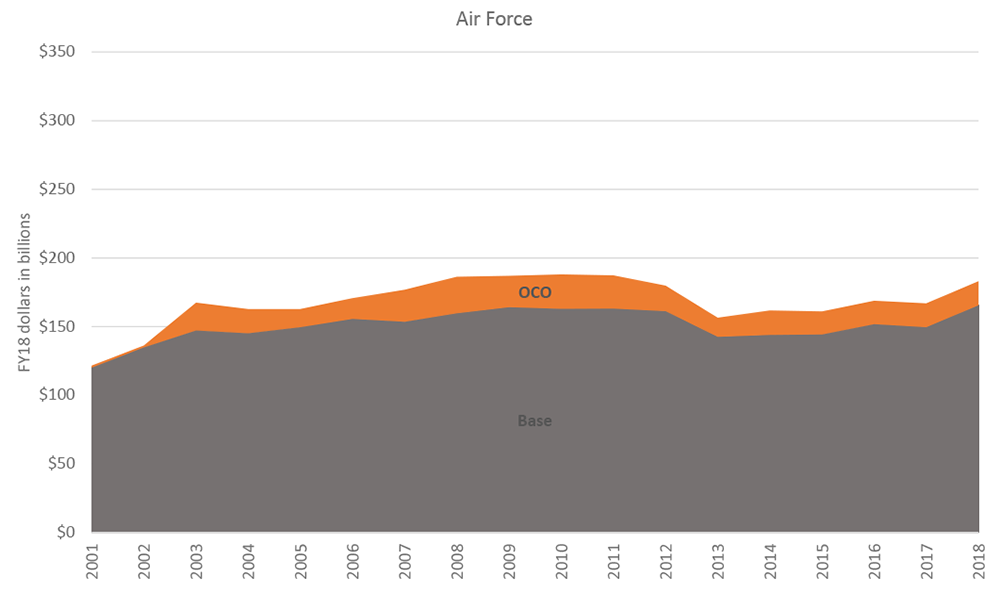

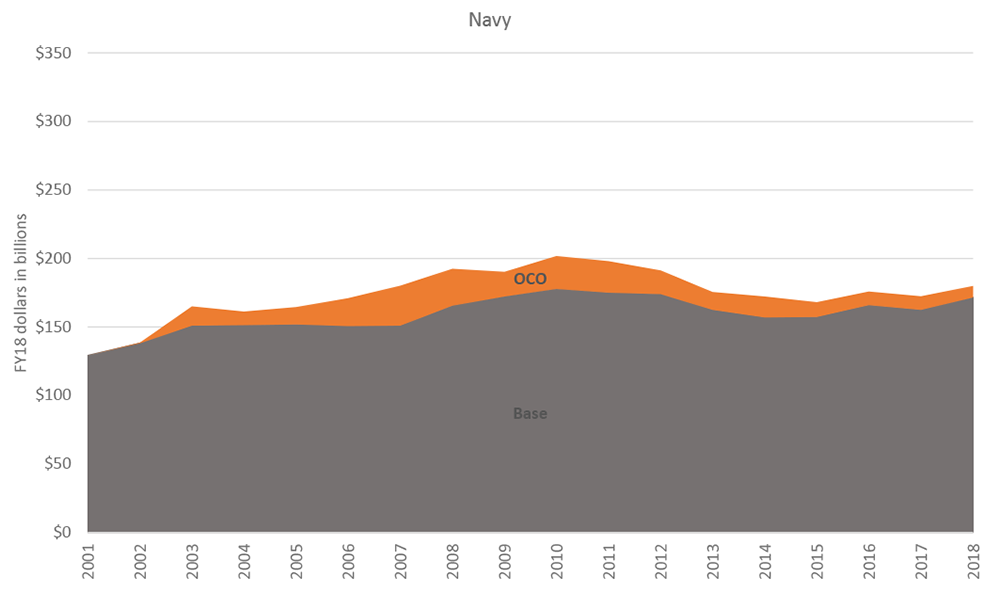

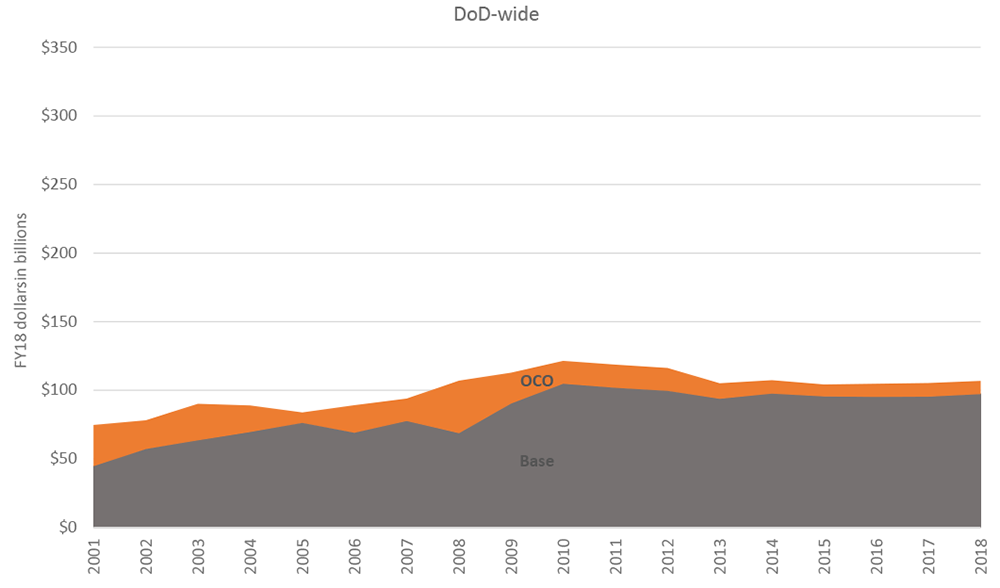

A final major difference between defence spending today and the FY 1979–FY 1985 defense buildup is the modern invention of OCO funding, which has get an essential component of the overall DoD upkeep. After the enactment of the Budget Control Act of 2011 and the imposition of caps on base discretionary national defense funding, only not on "emergency" funding, OCO has functioned equally a condom valve for the overall DoD budget. At $64.half dozen billion, the FY 2018 asking for funding of ongoing military operations is about 10 percent of the total DoD asking for $647 billion. The overall level of OCO funding has declined by two thirds between the FY 2008 top of $218 billion and the FY 2015 level of $66 billion, but has remained consistent at between $61.2 and $66.two billion since then. Overall, state of war funding comprises a much smaller share of the total DoD budget than it did during the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In FY 2007 and FY 2008, state of war funding accounted for 28 percent of the total discretionary DoD budget, simply it has stabilized at well-nigh 10 per centum of total discretionary DoD funding since FY 2015 (come across Figure nine-13). The Services rely on OCO funding to different degrees. OCO makes up 17 percent of the Regular army's total FY 2018 budget request, higher than any of the other Services, simply a decline from FY 2007, when OCO made up 49 percent of the Regular army'southward total budget. OCO accounts for 10 percent of the Air Forcefulness's FY 2018 asking, a relatively steady proportion since FY 2012. The Navy is the Service that is least reliant on OCO funding; information technology accounts for just five pct of the Navy'due south FY 2018 request, downwardly from 16 per centum in FY 2007. Nine per centum of the FY 2018 defense-wide spending is for OCO funds, downwardly from 36 percent in FY 2008 (come across Figure ix-fourteen). According to estimates by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and senior defence force officials, approximately $20–xxx billion of expenses properly considered base upkeep expenses are funded out of the OCO accounts. GAO has recommended that DoD revise the outdated 2010 Office of Management and Budget criteria for determining which defense costs can properly exist considered OCO, potentially limiting the corporeality of base budget costs that can be funded via OCO.[7] However, shifting the total $20–xxx billion enduring costs currently paid for through OCO back to the base upkeep would strain base Service budgets further.

Effigy ix-13: OCO As a Proportion of Total Discretionary DOD Upkeep

Source: OUSD, FY 2018 Greenbook. Calculations by CSBA.

Figure 9-fourteen: OCO As a Proportion of Service Budgets

Source: OMB, Historical Tables, Budget of the United States Regime, Financial Year 2018, Tabular array i.3. Calculations by CSBA.

1 of the most difficult balancing acts in the coming years will be between sustaining current operations while investing in the capabilities and technologies needed to deter, and if necessary fight and win, future wars. Fundamental armed services challenges and competitions—predominantly countering Russian and Chinese anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities, merely including the proliferation of precision strike capabilities and the contestation of infinite and the electromagnetic spectrum—volition play an important role in shaping warfare in the coming decades, especially in how the armed forces fights and what capabilities DoD will need to invest in. Maintaining the ability to operate in an environment where adversaries are capable of launching dense salvos of precision guided weapons requires a shift away from expensive long-range interceptors and toward both kinetic and non-kinetic short-range air and missile defense systems, boxing management and fire control systems besides as electronic warfare systems to deceive and degrade adversary capabilities. A2/AD capabilities will put a premium on being able to operate and deliver strikes over longer ranges. Developing networked cross-domain sensing, targeting, and striking capabilities across the joint forcefulness will require investment in C4ISR, electronic warfare, sensors, and long-range strike weapons. Operating in more highly contested environments, much dissimilar from the largely permissive environments of the past decade and a half of conflict, places a premium on systems that are either depression-observable (for high-value systems) or unmanned expendable systems.[8] At the same time, many of the missions U.S. forces conduct today, and are likely to go along conducting in the hereafter, occur in more permissive environments where these avant-garde capabilities may non be needed, sparking discussion on the right loftier-depression mix of capabilities. Additionally, today'due south military is facing chapters challenges, with the current operational tempo straining the Services. However, adding additional end strength, planes, and ships to relieve the operational tempo burdens would also require substantial boosted funding.

Senior Pentagon and armed services leaders, including Secretarial assistant Mattis, General Dunford, and the chiefs and vice chiefs of staff of each of the armed services Services have forcefully argued for more defense spending beyond FY 2018 in order to invest in the military capacity and capabilities needed now and for the time to come. Merely as important, they have emphasized that the Pentagon needs stable, predictable, long-term funding.[9] At a three percent CAGR, base of operations national defense force spending would reach about $670 billion in FY 2022. At 5 percent, it would accomplish about $755 billion, and at 7 percent, it would reach $845 billion. Those spending levels would exist between xx and 50 percent higher than the FY 2017 levels. Notably, General Dunford testified that iii–seven pct almanac growth would be sufficient for necessary capability investments, but insufficient to increment the Services' force structure or finish strength. The extant tensions between investing in capacity today vs. high-end capabilities for tomorrow volition but grow more acute if the Congress is unable to bridge their sharp differences on fiscal policy and defense and non-defense spending to eliminate the BCA caps. Although it invests in improved readiness via increased grooming funding, maintenance funding, and healthier spare parts stockpiles and amps upwards investments in RDT&E, the FY 2018 budget continues to straddle this divide, postponing anticipated investments in capacity until FY 2019 and beyond.

Figure 9-fifteen: Notional 3%, five%, and 7% Almanac Increases in Defense Spending Above FY18 Request Levels

Source: Office of Management and Budget, FY 2018 Budget, "Table 25.1, Internet Budget Authority by Function, Category and Programme." Calculations past CSBA.

![]()

ABOUT THE Writer

Katherine Blakeley is a Research Swain at the Heart for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Prior to joining CSBA, Ms. Blakeley worked equally a defense policy analyst at the Congressional Inquiry Service and the Center for American Progress. She is completing her Ph.D. in Political Scientific discipline from the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she received her M.A. Her bookish research examines Congressional defence policymaking.

ABOUT THE Heart FOR STRATEGIC AND Budgetary ASSESSMENTS (CSBA)

The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy inquiry constitute established to promote innovative thinking and debate almost national security strategy and investment options. CSBA's analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource resource allotment.

NOTES

[i] Joe Gould, "Thornberry Wins Pledge to Abound DOD Budgets, Simply Will It Stick?" Defense News, June 27, 2017, bachelor at https://world wide web.defensenews.com/congress/upkeep/2017/06/27/thornberry-wins-pledge-to-grow-dod-budgets-but-will-it-stick/.

[2] Tony Bertuca, "Dunford: DOD Needs Betwixt iii Pct and seven Percent Growth Annually," Inside Defense, September 26, 2017, available at https://insidedefense.com/daily-news/dunford-dod-needs-betwixt-3-per centum-and-7-percent-growth-annually.

[3] This defense investor sentiment was relayed in electronic mail newsletters from Capital Alpha Partners.

[4] For an excellent overview of the evolving national security analysis of shifts in the international strategic landscape and security environment over the past several years, see Ronald O'Rourke, A Shift in the International Security Environs: Potential Implications for Defense, R43838 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, August sixteen, 2017), Appendix A, "Articles on Shift to New International Security Environment."

[5] The 1981 tax cuts were enacted by the Economical Recovery Revenue enhancement Act of 1981 ,P.L. 97-34.

[6] Gallup News, "Military and National Defense," polling conducted Feb 1–5, 2017, bachelor at http://news.gallup.com/poll/1666/military-national-defense.aspx.

[7] Government Accountability Office (GAO), Overseas Contingency Operations: OMB and DOD Should Revise the Criteria for Determining Eligible Costs and Identify the Costs Likely to Suffer Long Term, GAO-17-68, report to congressional requesters (Washington, DC: GAO, January 2017), available at http://world wide web.gao.gov/assets/690/682158.pdf.

[viii] For discussion of strategic approaches in the evolving international security mural and future military operational challenges, concepts, and capabilities, meet selected contempo CSBA reports Preserving the Residual: A U.S. Eurasia Defence force Strategy, by Andrew F. Krepinevich; Avoiding a Strategy of Bluff: The Crisis of American Military Primacy, by Hal Brands and Eric Edelman; Dealing with Allies in Decline: Alliance Management and U.S. Strategy in an Era of Global Power Shifts, past Hal Brands, and Extended Deterrence in the Second Nuclear Age, by Evan Montgomery. For discussions of time to come military competitions and U.Southward. operational concepts and capabilities, see Restoring American Seapower: A New Armada Compages for the U.S. Navy, past Bryan Clark et al.; Wining the Salvo Competition: Rebalancing America's Air and Missile Defenses, past Marking Gunzinger and Bryan Clark; Trends in Air-to-Air Gainsay: Implications for Future Air Superiority, by John Stillion; Winning the Airwaves: Regaining America's Authorisation in the Electromagnetic Spectrum, by Bryan Clark and Mark Gunzinger; What it Takes to Win: Succeeding in 21st Century Boxing Network Competitions, by John Stillion and Bryan Clark; and Toward a New Start Strategy: Exploiting U.South. Long-Term Advantages to Restore U.South. Global Power Project Capability, past Robert Martinage.

[9] General Daniel Allyn, Vice Master of Staff United States Regular army; Admiral William Fm. Moran, Vice Chief of Naval Operations; General Glenn Walters, Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps; and General Stephen West. Wilson, Vice Principal of Staff of the Air Forcefulness, "Current State of Readiness of the U.S. Armed Forces," Statements before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Subcommittee on Readiness and Management, February viii, 2017; and General Mark Milley, Main of Staff Usa Army; Admiral John M. Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations; General Robert B. Neller, Commandant of the Marine Corps; and General David L. Goldfein, Chief of Staff of the Air Strength, "Impacts of a Year-Long Continuing Resolution," Statements earlier the House Military Commission, April 5, 2017.

Source: https://csbaonline.org/reports/defense-spending-in-historical-context

0 Response to "what happened to american defense spending under president reagan?"

Postar um comentário